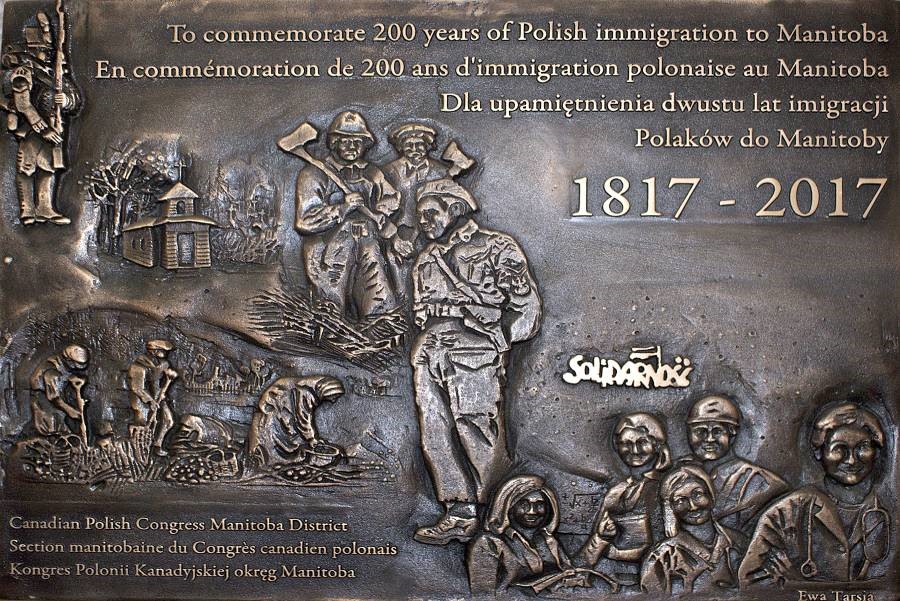

200 years of immigration of Poles to Manitoba

Photo: Mirek Weischel

1817 – 2017

I

The first Poles to arrive in Manitoba were a group of soldiers from the De Meuron regiment, who came to the Red River settlement with the Lord Selkirk expedition in 1817.

The ten Polish men who arrived on the banks of the Red River with the Lord Selkirk expedition joined the British army after the defeat of Napoleon Bonaparte. Thousands of Poles served and fought under Napoleon, hoping to reestablish Poland’s independence, lost in 1795 after the last partition of Poland by Austria-Hungary, Russia, and Prussia. After Napoleon’s defeat, those who were captured by the British became prisoners of war, and most were imprisoned in an old warship in deplorable conditions. Their only hope for freedom was to volunteer for service in foreign regiments, such as De Waterville and De Meuron. Eventually, they were brought to the American continent to fight for the British cause, and many of them fought in the War of 1812 against the United States. A good number deserted the British ranks, believing that the American cause was a just one; those who remained continued to fight for the British.

In the early 19th century, a rivalry broke out between the Hudson’s Bay Company and the North West Company for the control of the lucrative fur trade. In 1816, to oust the competition, the North West Company took some extreme measures that resulted in the loss of life. This prompted Lord Selkirk, who owned a large tract of land along the Red River, to take direct action. He recruited volunteers from the De Waterville and De Meuron regiments, including ten Poles, to restore order and provide protection to the Red River colony. By offering sizable portions of land and monetary incentives, Lord Selkirk was hoping to settle the Poles on the banks of the Red River. They arrived at the colony in June 1817. The ten Polish recruits were Michel Bardowicz, Pierre Gandroski, Andrew Jankowski, Michael Kaminski, Martin Kralich, Wojciech Lasotta, Laurent Kwileski, John Wasilowski, Michel Isaak and Antoine Sabatzki. A monument dedicated to them has been erected in Birds Hill Park, just outside Winnipeg. The censuses of 1832 and later indicate that only four of the ten Poles actually settled; the rest departed, after the great flood of 1826, for other parts of Canada or, perhaps, for the United States. Those who stayed were Michel Bardowicz, Pierre Gandroski, Andrew Jankowski, and Michael Isaak.

Only a very small number of Poles made Manitoba their home between 1817 and 1895. The most prominent among them were Edwin Brokowski, a surveyor and publisher of the Manitoba Gazette and Trade Review, and Charles Czerwinski, the proprietor of the Czerwinski Box Company. It was around 1895 that a large wave of new immigrants — Poles among them – began to arrive in Manitoba.

II

The first wave of Polish immigrants, during the pioneer era, started with mass migration from continental Europe in the 1890s and lasted until the outbreak of WW I in 1914. It resumed in 1919 and continued until the outbreak of WW II in 1939.

As immigration from England and Ireland stalled at the end of the nineteenth century, the largest wave of immigrants from continental Europe began arriving on North American shores. The Canadian Pacific Railway and the Canadian government were actively looking for new settlers to populate the vast territory of Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta, as the country was expanding westwards. The resulting influx of immigrants – more than three million between 1891 and 1914 – was facilitated by the changes to the immigration policy introduced by the government of Sir Wilfred Laurier and implemented by Sir Clifford Sifton, Minister of the Interior. Agents from various shipping companies were sent out to Europe in order to attract and recruit anyone willing to settle in the West on the promise of free land and good remunerative jobs, either building the railroad or working in the newly established mines. The agents portrayed Canada as a land of unlimited opportunities with a bright future. The new immigrants were mostly poor peasants from overpopulated areas of continental Europe, living under very poor economic conditions. The largest group came from the area called Galicia, in the Austro-Hungarian Empire; others came from the Prussian- and Russian-controlled portions of former Poland. Among the many ethnic groups migrating to Canada was also a sizable contingent of Poles. The key factors in their decision to emigrate were probably political restrictions and high taxation in their homeland. They were attracted to Canada by large allotments of land and a promise of better living conditions.

Reality, however, proved to be much different. Almost all of them were ill prepared for its challenges. The Polish settlers soon discovered that life on the prairies was harsh and difficult. They faced new and unforeseen challenges of the land – infestations of mosquitoes and other insects, swampy areas, thick and dense bush. Initially, they constructed primitive shelters, such as dugouts or sod cabins, which they later replaced with more solid log houses, providing more stable and secure shelter against the elements.

At the beginning, their lives demanded arduous manual labour. Clearing the forests, building primitive dwellings, and breaking the land with oxen and primitive tools made their life brutally hard. Traveling to cities to sell the produce sometimes took days. Lack of fluency in English and unfamiliarity with English customs added to the challenges. Overcoming such hardships demanded courage, determination, and perseverance. Many gave up and returned to their homeland, while others felt trapped, too poor to buy return tickets. Those who stayed and persevered, slowly built new lives for themselves and adjusted to the realities of Manitoba. During those difficult times, it was their faith and their church that provided them with spiritual guidance and moral support; eventually, most of them not only survived but prospered.

III

After the end of WW II (1945), many Poles were scattered across the European continent. Soldiers of the Polish 2nd Corps, who fought alongside the Allied Forces, constituted the largest group. They could not return to their homeland because it was controlled by what they considered to be a hostile government. Instead, they requested and obtained permission to come to Canada, and some of them settled in Manitoba.

On September 1, 1939, German troops invaded Poland, starting World War II in Europe. Thousands of Poles were rounded up by the Nazis and by the Soviets who invaded Poland a few weeks later; they were sent to German concentration camps and Soviet labour camps in Siberia. With the outbreak of German-Russian hostilities in June of 1941, the Soviets released all Poles from the camps. As part of an understanding between the Polish and Soviet governments, a new Polish army was to be formed on the Soviet territory to fight alongside the Red Army. However, since the Soviet government was unable to deliver the necessary supplies and military equipment, the Polish government in exile decided to evacuate all Polish soldiers to the Middle East. The result was an exodus from Russia of more than 100,000 Polish military personnel and civilians, including thousands of children. Eventually, the Polish soldiers formed the Polish 2nd Corps that became part of the British 8th Army, under the command of Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery. The Army took part in the Italian campaign and fought one of the decisive battles of WWII, the battle of Monte Casino. After 1945, the soldiers of the Polish 2nd Corps found themselves in limbo. With the Communists in charge of the government in Poland, the majority decided not to return to their homeland in fear of reprisals. An understanding between the Polish government-in-exile and the British government was reached whereby thousands of Polish ex-servicemen were allowed to emigrate to different parts of the British Commonwealth and South America, with a good number coming to Canada and Manitoba. Still wearing Polish military uniforms, they arrived to begin a new life. Although more educated and better equipped to settle in their new homeland than their predecessors, they too experienced their share of hardships. As part of the agreement, they had to fulfill a two-year contract requiring them to work in the fields or as lumber jacks in the forest. Completing the requirement qualified them to stay in Canada permanently. They arrived in Canada with their own combatants’ organizations and devoted themselves to raising a new generation and continuing the fight for Polish independence. They supported and maintained the Polish language, traditions, customs, and important anniversaries, preserving their Polish identity while becoming part of their adoptive homeland.

IV

The last wave of Polish immigrants arrived in Manitoba in the 1980s, during the Solidarity period. The word “Solidarity” became synonymous with freedom and symbolic of the Polish desire to regain full independence from the Soviet Union.

At the end of WWII, Poland fell under the influence of the Soviet Union, which imposed Communist ideology and installed a Communist state, a political system resented by the majority of Poles. Several attempts to challenge that system ended in failure. However, in the early 1980s, with the moral support of Pope John Paul II, Poles openly confronted the Communist government by launching the “Solidarity” movement. This resulted in a clash with the authorities and eventually led to the imposition of martial law on Dec 13, 1981. With an uncertain future and political instability at home, thousands of Poles sought new and better life in other parts of the world. Canada – including Manitoba – opened its doors to many of them. Those latest arrivals came from all walks of life, but they were usually well educated. With perseverance and determination, many became successful in their adoptive homeland and managed to re-enter the work force in their former professions as doctors, engineers, teachers, tradesman and others. Today, many of them are employed in a variety of industries, contributing to the development of Manitoba and Canada. The most iconic symbol of that era is the name of their movement, “Solidarity”, with which this wave of Polish immigrants is always identified.

Autor-Lechosław Gałęzowski